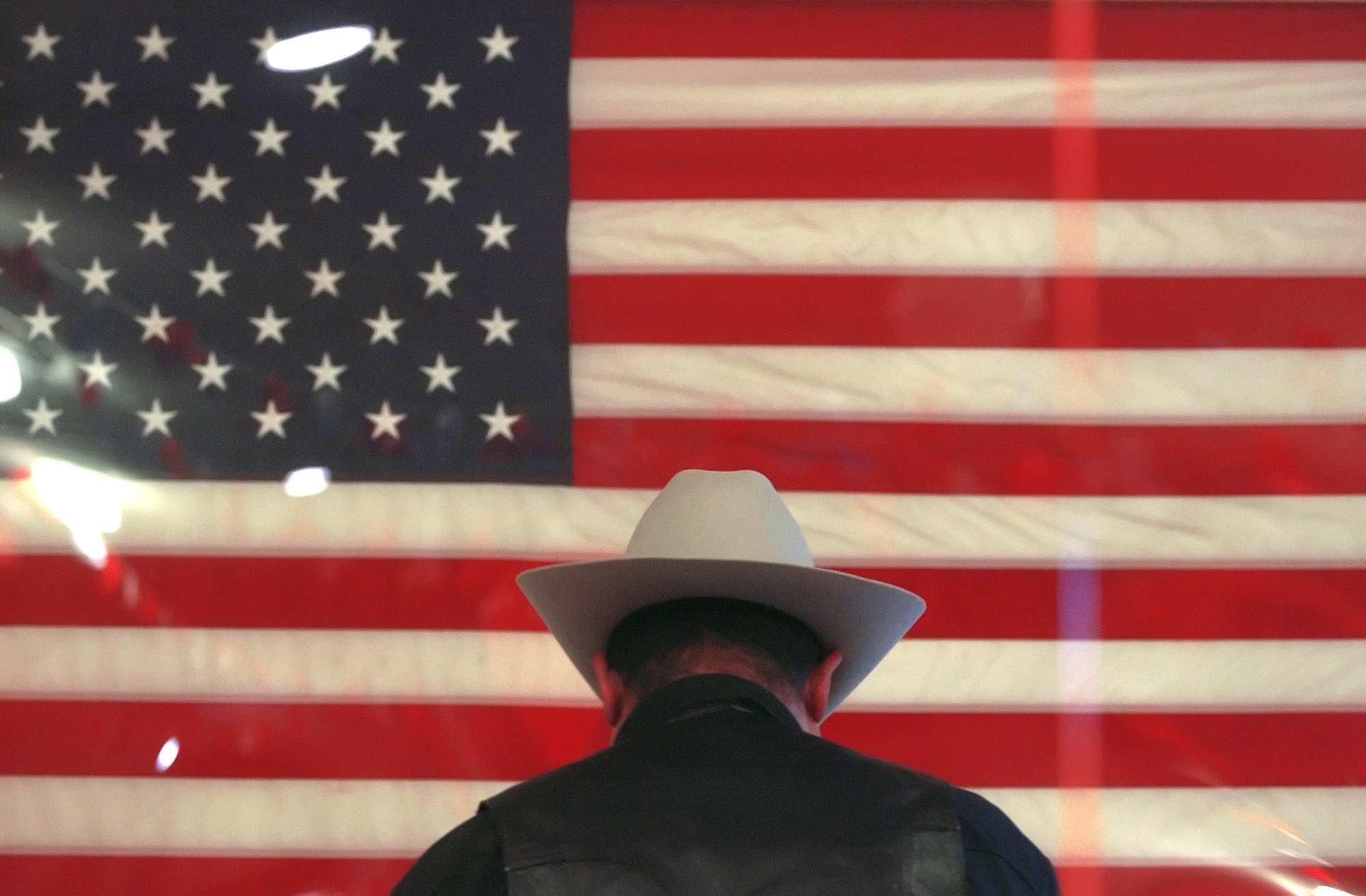

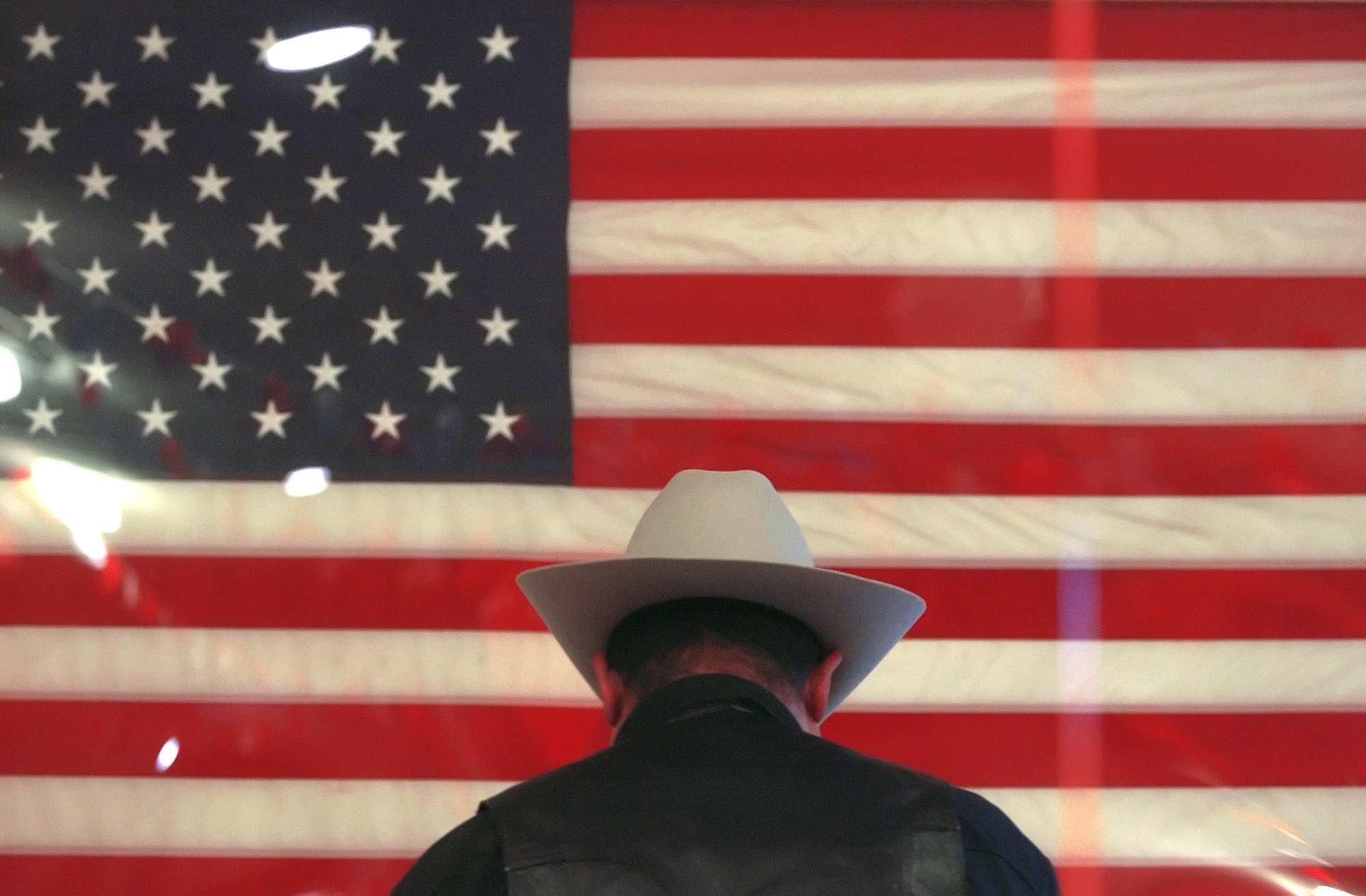

They come from Florida, Texas and nearly every region of Mexico. Some have ventured to Northwest Michigan for decades, returning each harvest to pick fruits and vegetables. During the 1950's, Grand Traverse County was home to the largest migrant population of any county in the country - numbering over 30,000. Today, fewer than 2,000 migrants return to Grand Traverse's seasonal work in the orchards and vineyards. Few have permanently settled, however, a small minority of migrants are deciding their future remains in the U.S. and Northwest Michigan. Above, a man dressed in traditional Tejano attire, attends a Quinceanera, or 15th birthday celebration hosted for girls in Mexican and Mexican-American culture. (Tyler Sipe / Traverse City Record-Eagle, 2006)

The Salinas and Gonzalez family, three generations of migrants, retired early from work in the fields to watch Mexico play Angola during the World Cup Soccer Tournament. The family migrates from the Rio Grande Valley of Texas each year to work in the areas vineyards and fruit processing plants.

Gustavo Magana, a native of Michoacan, Mexico, carries a bag of McIntosh apple's to a crate while working at Ocanas Farms on the Old Mission Peninsula. Magana has picked for nine seasons at Ocanas Farms. He works 10 to 12 hours a day alongside seven others picking an estimated 1.5 to 2.5 million pounds of apples. An estimated 40,000 migrants work in seasonal labor in Michigan.

From left, Ramiro Zepeda and Raul Vazquez, both from the Mexican state of Guanajuato, laugh and relax while enjoying a lunch break at a 5,000-acre Christmas tree farm in Manton. Both Zepeda and Vazquez send most of their income back home to their families and a small portion to a non-profit organization in their hometown. Mexican laborers and expatriates sent over $20 billion in remittances to Mexico in 2005.

Benito clips grape vines in 30 degree temperatures on the Old Mission Peninsula outside of Traverse City. The 51-year-old was born in the south of Mexico and has lived in Traverse City for the past four years. He has lived in the United States as an undocumented migrant for the past quarter century. He moved to this country to help support his wife and four children. Back in Mexico, he worked 50 hours a week in a rock quarry earning $1.50 an hour gathering marble that was eventually made for commercial tiles headed to the United States. He now earns substantially more working the fields around Traverse City, making about $9.50 an hour by pruning and maintaining grape bushes for the area's growing wine economy.

Gabriel Molina, left, watches television while Jose Guadalupe speaks on the phone to his wife Marion Guadalupe who resides in Urireo, Mexico. Guadalupe and dozens of other migrants at Dutchman Tree Farms spend about eight months away from home and family. They send most of their income to loved ones who depend on their salaries.

Old Mission Peninsula farmer Leo Ocanas waits for several dozen crates of McIntosh apples to be unloaded at the Peninsula Fruit Exchange on the Old Mission Peninsula. Ocanas, once a migrant, depends on migrant labor to assist him with the 750,000 pounds of cherries and 2.5 million pounds of apples he harvests annually. During most years, Ocanas has the help of a dozen-plus migrant workers from Michoacan, Mexico, who assist in the harvest. This year, Ocanas welcomed only eight workers to his 200-acre farm, and their arrival was three months late. The 61-year-old cited the recent national debate on immigration policy - often divisive and inflammatory - as a reason for the labor shortage and delays. As a result, the 61-year-old worked 18 to 20 hours a day during peak cherry season.

Traverse City West sophomore Jose Flores, 15, hangs a last minute decoration while senior Mayani Salinas, 18, practices a dance routine prior to a Cinco de Mayo dance performance. Eight Mexican-American students from West performed several traditional Mexican dances for students, faculty, and community members. The students practiced for over two weeks and held the Cinco de Mayo celebration to give their peers a better understanding of their culture and diversity. "What I want them (audience members) to learn about Cinco de Mayo is that Mexicans have really good traditions, and music, and food," Flores said. "I want them to learn that in Mexico, we are always supporting each other. We are helping (each other) with our hands."

Seven-year-old Belia eyes Anayeli prior to Anayeli's Quinceanera in Traverse City. A Quinceanera is an important and lavish Mexican cultural tradition marking the 15th birthday of a young girl. It symbolizes the transition from girlhood to becoming a woman. Anayeli's Quinceanera brought together over 300 people from the migrant and agriculture community.

Romelia Magana, center, and Kim Sanchez, right, carry a portrait of the Virgin of Guadalupe and lead about 75 people to celebrate the Mexican holiday Our Lady of Guadalupe at St. Joseph Rectory on the Old Mission Peninsula. It is customary in Mexico for people to take a portrait of the Virgin of Guadalupe on a pilgrimage from house to house prior to the start of the official holy day held on December 12. The Virgin of Guadalupe appeared to peasant Juan Diego in December, 1531. The event is significant because it bridged two cultures, the "New World" explorers and the indigenous people of the Americas. The holiday and the Virgin of Guadalupe is of particular importance for individuals with Mexican ancestry.

First and second graders in Brenda Schwind's class participate in an English and grammar lesson at the Benzie/Leelanau Migrant Summer School located at Suttons Bay Elementary. In 1972, there were 11 migrant schools stretching from Mason County in the south to Charlevoix in the north, serving over 5,000 migrant students from mostly Florida, Texas and Mexico. Today, only two schools remain with a combined enrollment of about 250 students.

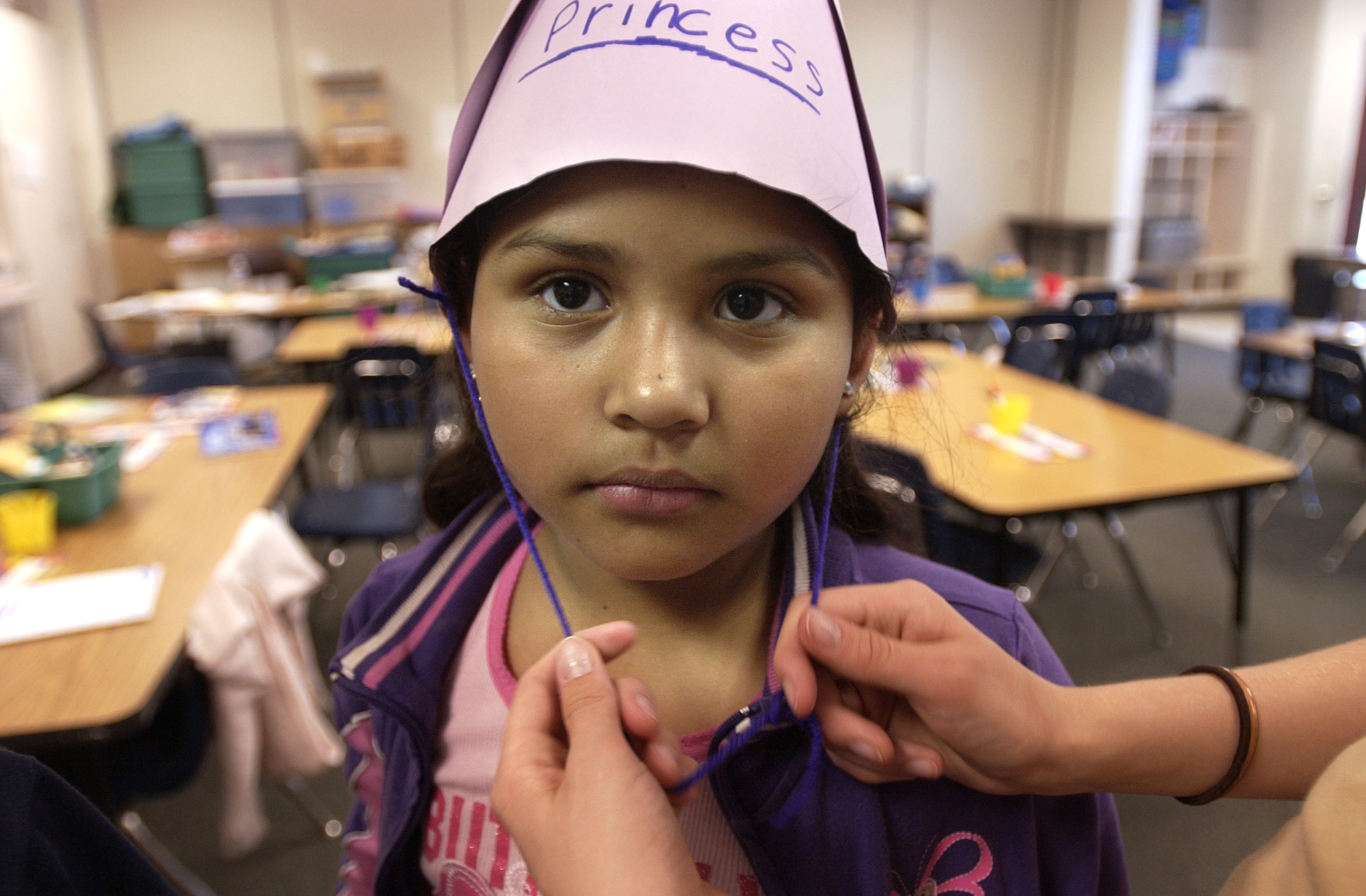

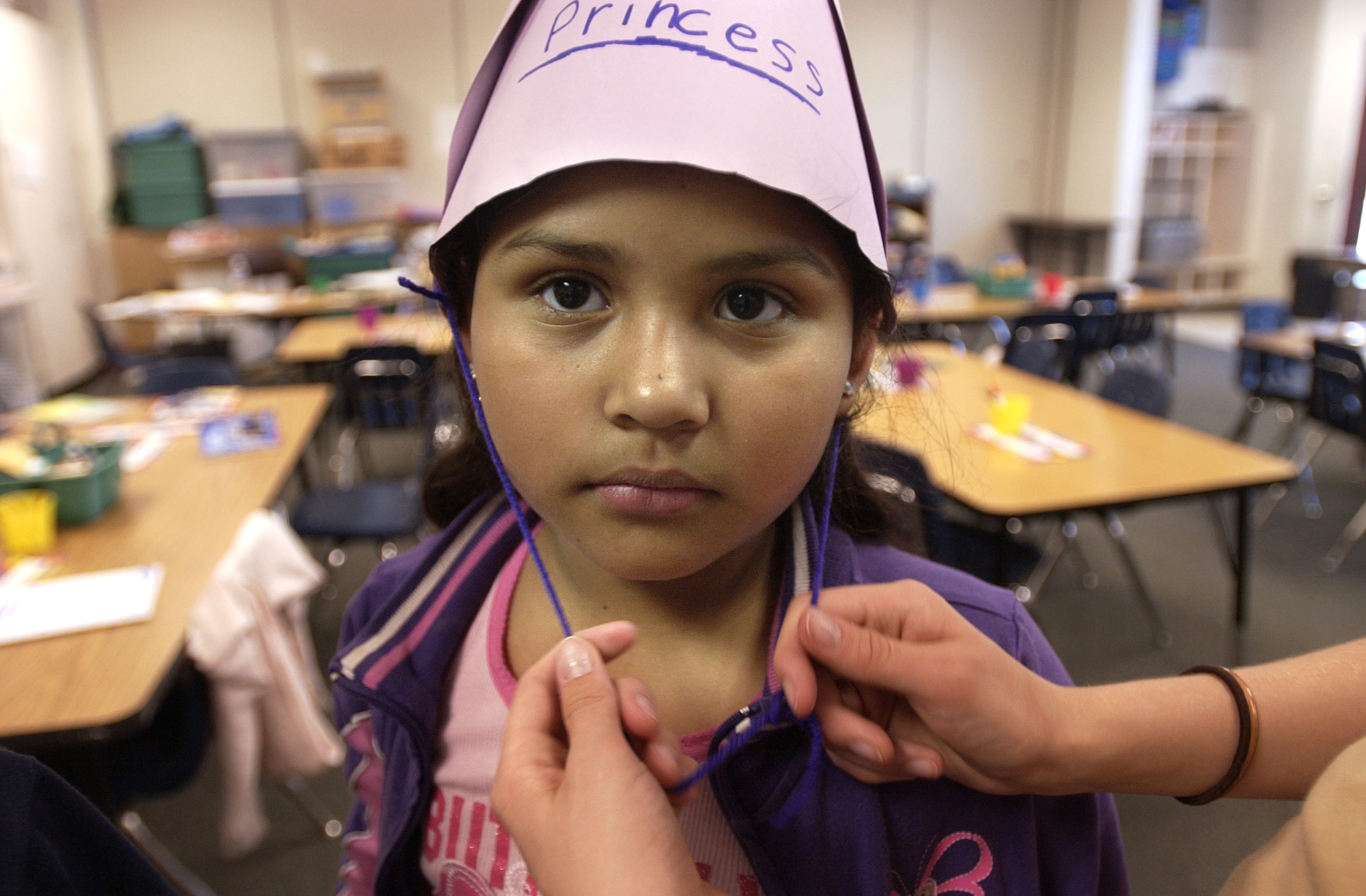

Eight-year-old Karen Martinez has assistance with her hat by aide Lauren Gusler prior to a 'Fairy Tales' poem performance for third and fourth graders at an ESL school for migrants at Suttons Bay Elementary.

Eighteen-year-old Mayani Salinas and her uncle Ivan Salinas, 19, laugh and applaud one of their friends during their graduation ceremony at Traverse City West High School. Mayani and Ivan, both children of Mexican migrants, are the first in their family to earn their high school diploma.

A map of Northwest Michigan is tagged with about 120 locations of migrant camps and residential units in Antrim, Grand Traverse and Leelanau counties. There is an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 migrants living in seven Northwest Michigan counties. Approximately 2,000 live in Grand Traverse County.

Antonio Mosqueda, 9, and his cousin Miguel Mosqueda, 7, peer out the door while Andie Gonzalez, 22, completes a health survey with Antonio's mom Maria Isabel Mosqueda, right, at a migrant camp in Leelanau County. Gonzalez, and three other interns with Project Puente, surveyed 314 migrants and seasonal workers accounting for over 1,200 individuals in about 120 migrant camps in three counties. Gonzalez, a migrant from Texas, spent the summer interning at Northwest Michigan Health Services.

Juleo Ramos, a documented resident immigrant, is greeted by family friend San Juanita Teeple, whom assisted Juleo's wife Lorena Ramos and daughter Emily Ramos, 3, with translation services at a doctor's office in Cadillac. Teeple grew up a migrant and now regularly assists Hispanics in the area with translation to overcome legal, medical, and societal barriers.

Francisco Nuno waves the American flag in celebration of wife Tomasa Nuno's during her participation in a naturalization ceremony of new immigrants at the Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park in Grand Rapids. Nuno, a native of Guerrero, Mexico has lived in Michigan for the past decade. Tomasa's husband Francisco Nuno, son Javier Nuno, and daughter Lorena Ramirez have all become naturalized, and their youngest daughter Patricia, 7, was born an American citizen. Nationally, immigration became a political hot button issue, which emboldened Tomasa to become an American citizen so she could vote in the 2006 mid-term elections.

Jessie Reyes holds up an old family portrait of his wife Isabel and three children. The family recently purchased 2.6 acres of property and had a 2,000 square foot home built near Suttons Bay. Jesus and Isabel have spent over 20 years migrating from the Rio Grande Valley of Texas to the fields of Michigan. Isabel moved to over 30 schools as a child and the couple decided after finding steady work and sending their eldest boy to college that they would permanently settle in Suttons Bay. "I think I'll stay here in Michigan for the rest of my life," Jessie said. "It's a better life for me and my children."